LIFESTYLES OF THE SECWÉPEMC

The Secwépemc people lived life by the moons. They lived in a seasonal round way. Each time of the year called for specific activities. They lived on a 13-month moon cycle rather than the 365.25 days around the sun. The moon orbits Earth every 28 days, which gives a 364-day year.

THE SECWÉPEMC CALENDAR

LIFE BY THE MOONS

PELLC7ELLCW7ÚLLCWTEN OR Entering Pithouses Month

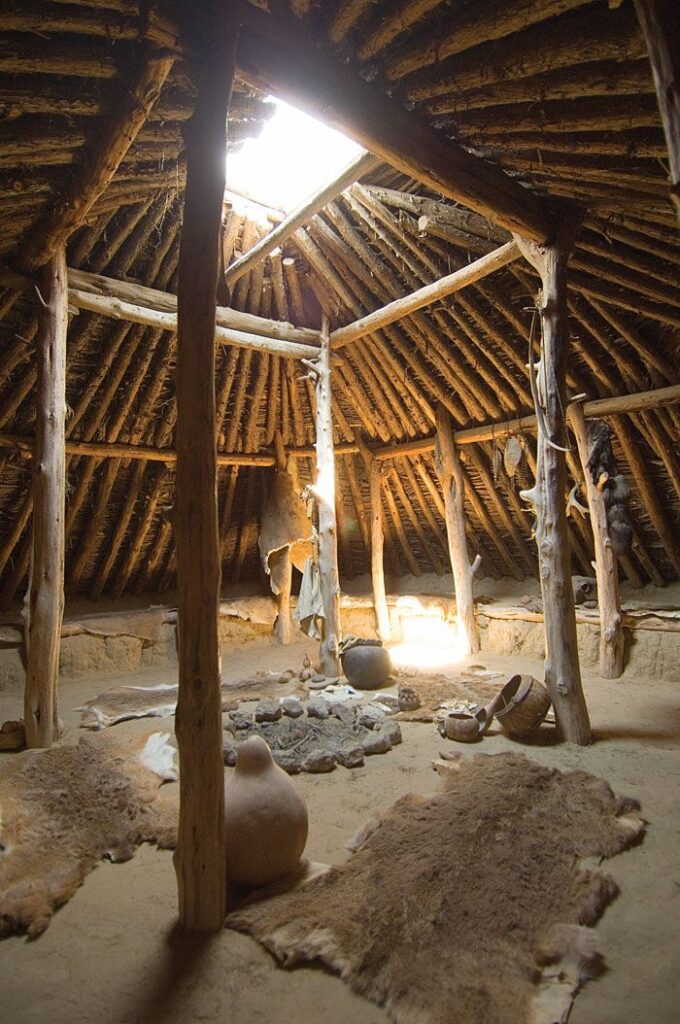

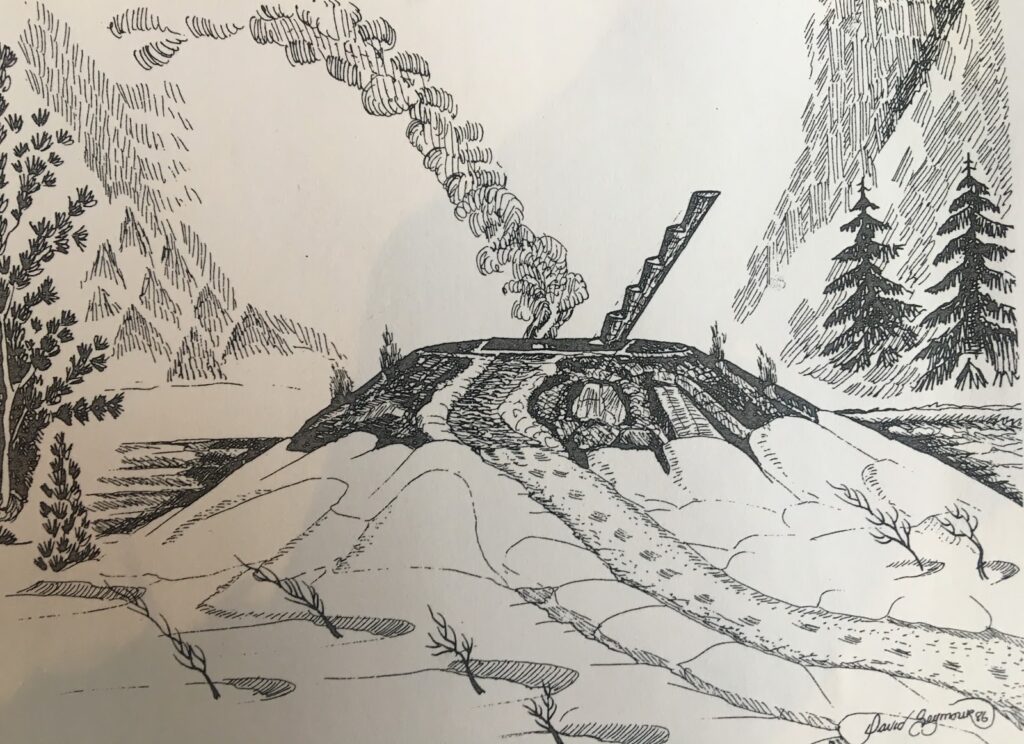

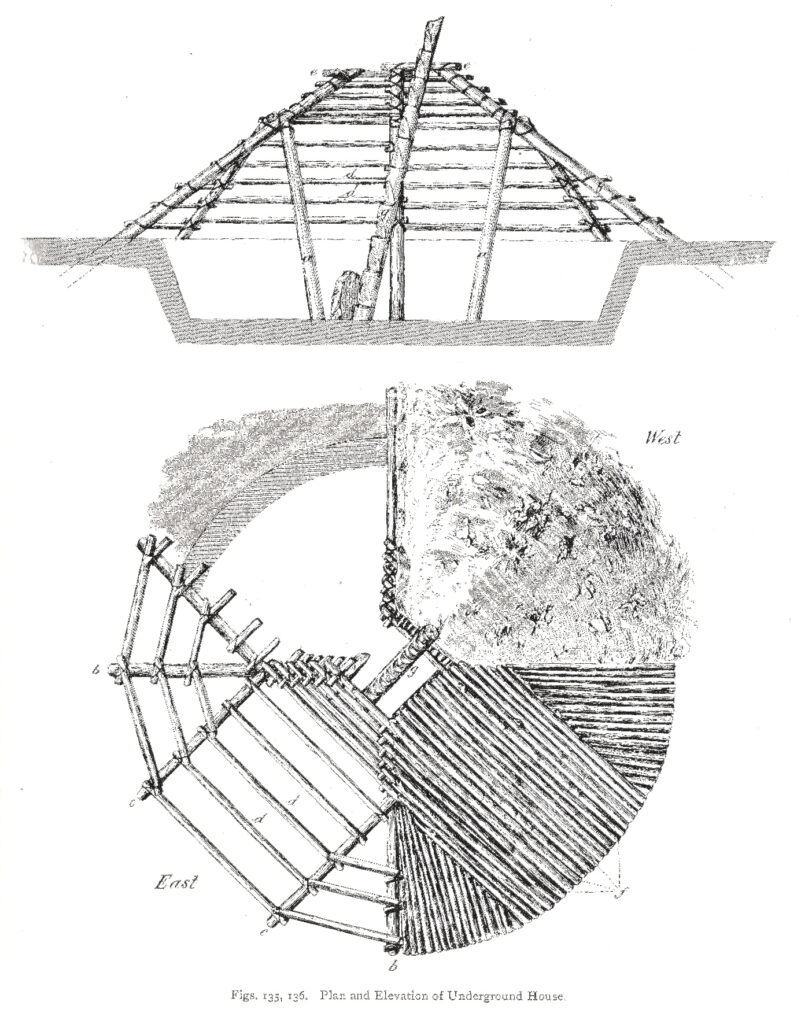

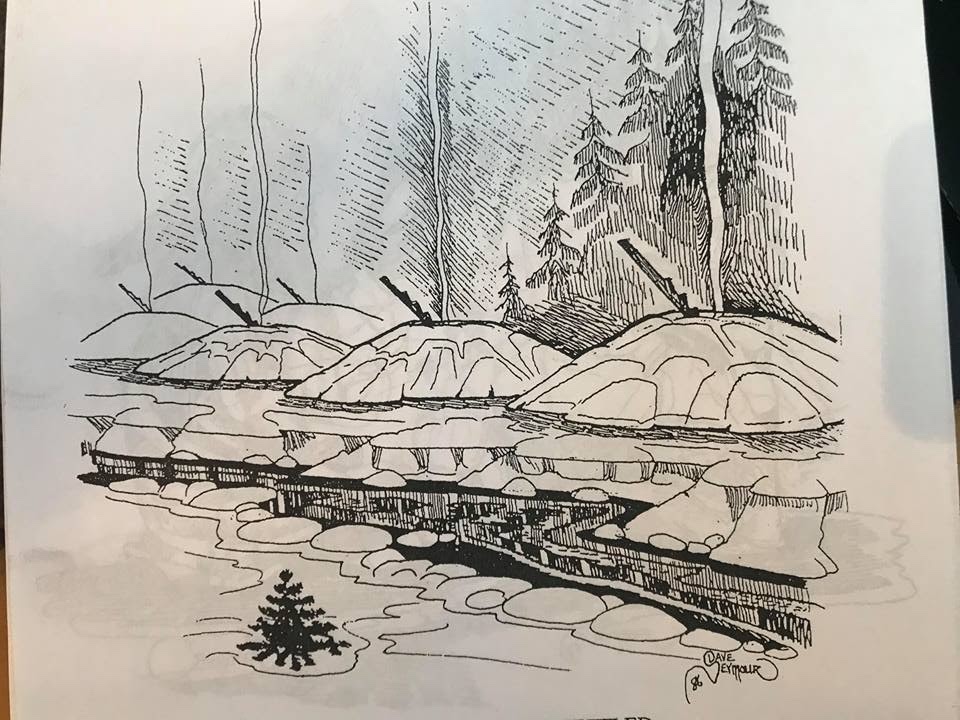

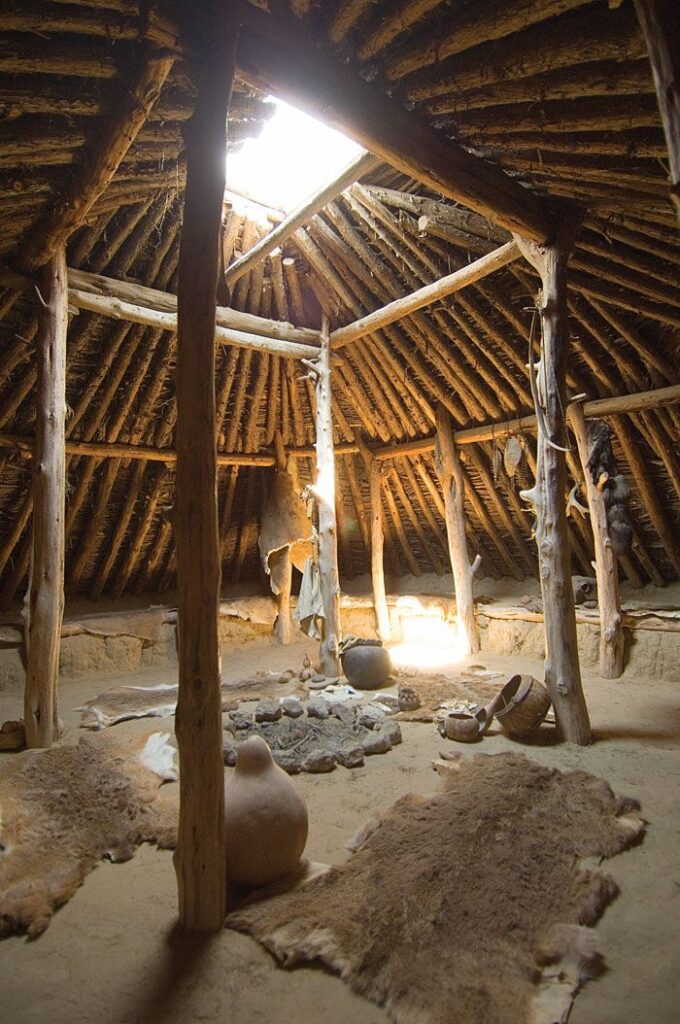

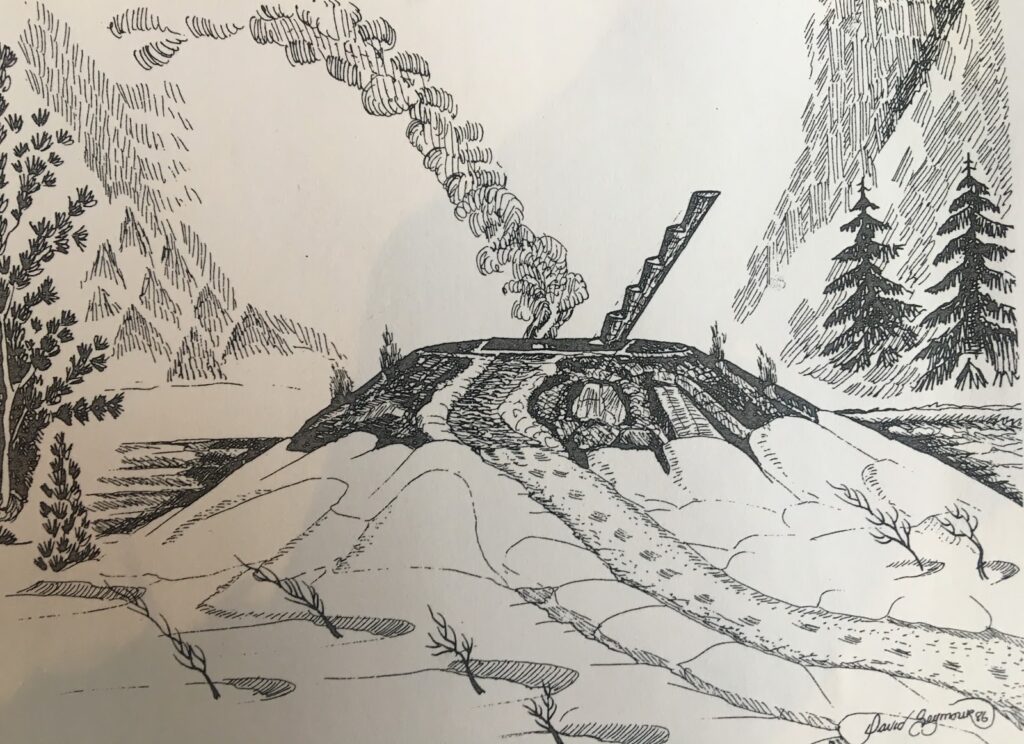

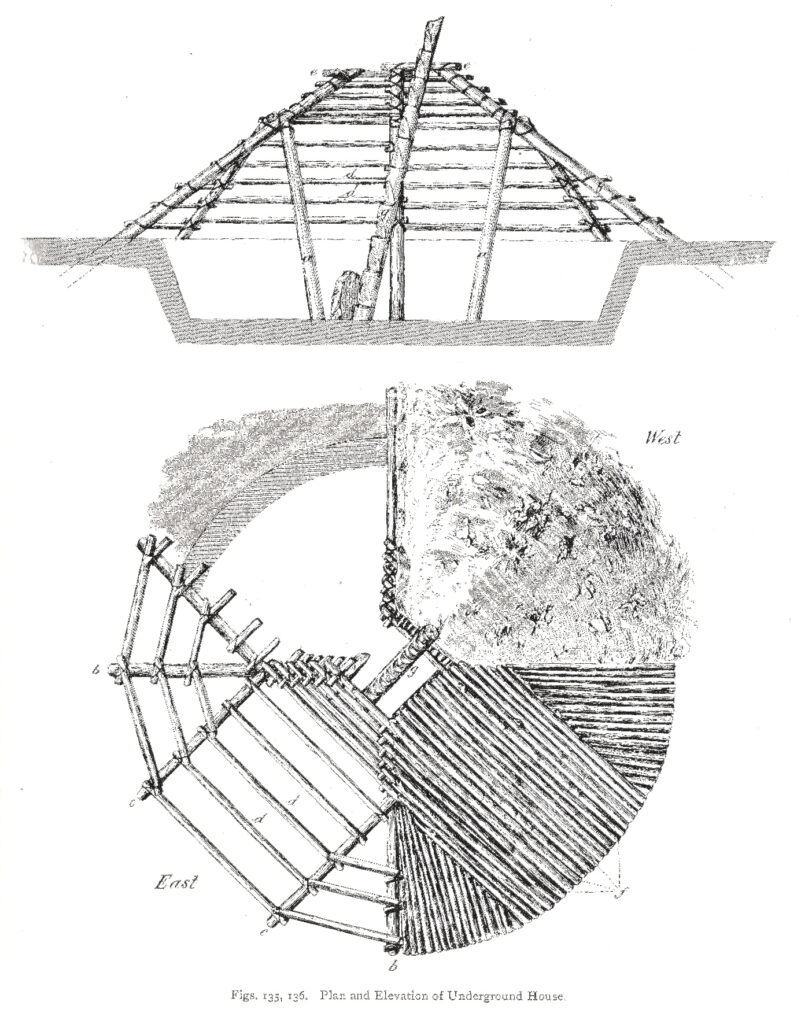

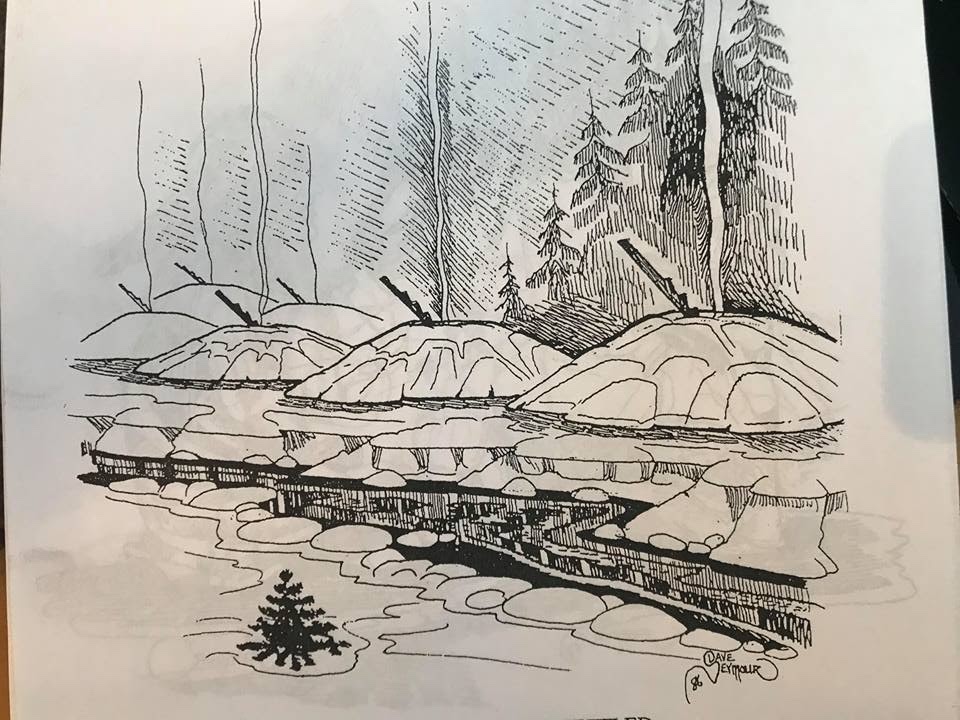

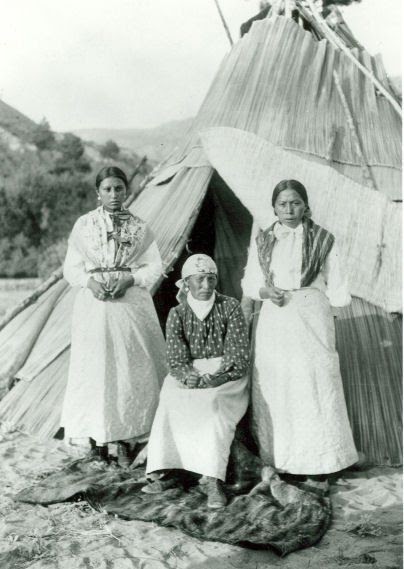

First Moon was when people moved into their winter homes. It was also the time when the deer ran, so some hunting was being carried out. The First Moon was in November, by our present calendar. At this time the Secwepemc people from all over moved into their winter villages by the rivers. Peoples’ caches, both above and underground, were located and filled with bounty of their summer and fall work. Here too, along the banks near the village, appeared the sweathouses, where they could regularly cleanse themselves, both physically and spiritually.

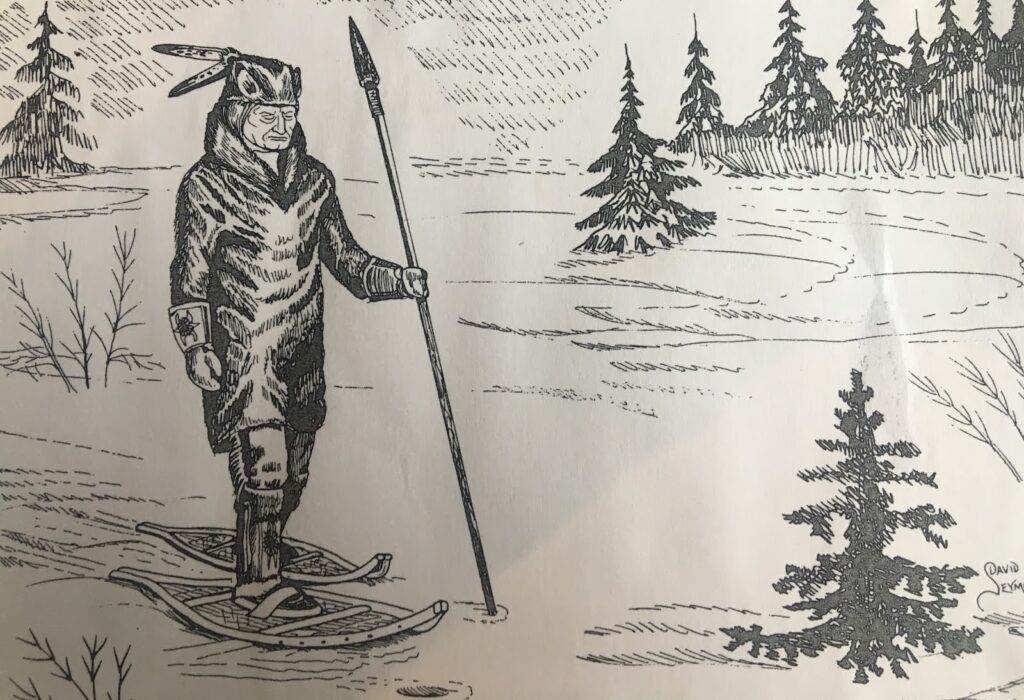

Along the Shuswap Lake, Canim Lake, the South Thompson, the North Thompson, and the Bonaparte River valleys, people were building or rebuilding winter dwellings that would be comfortable throughout the winter. When people had moved into their winter homes, the hunting chief would call the men to hunt elk or deer in the nearby hills. The hunters would travel in small groups and call the male game with bone calls or by imitating them, attracting the animals. The meat brought into the village was shared among the hunters’ families and dried above the fires, to be later added to the caches which held large supplies of winter food.

During this moon, storytelling would begin, to shorten the long evenings that were part of winter season. Precious chunks of dried strawberry or saskatoon cake could be enjoyed as the elders of the families spent hours telling the stories of their ancestors to the younger members. Young children would drift into sleep to the sound of their grandparents’ voice recounting the tales and truths of the Secwépemc way of life.

PELLTETÉQEM or Crossover Month

The Second Moon, was the time of first real cold, around December. At this time, people were well settled for winter. The men continued to go out on hunting trips alone or in small groups, bringing back more deer for drying and eating fresh. Women and children helped to set traps and snares for small animals near the village site, catching rabbits and other small animals. The food for a day of trapping might be a dried cake of meat and berries and some dried salmon.

Women took skins from storage and began work on the winter clothing and all garments needed for the coming year. Many hours were spent by the women, sewing together by firelight. Each day, women and children collected wood to keep the house fire burning and water from the lake or river, for cooking and cleaning. A constantly burning fire would warm deer meat stews and berry cake mixed with deer grease, or soups thickened with black tree lichen.

During this month a group of young would plan a visit, to a neighbouring village, or to other members of the same village. One was for the visitor to lower a bundle into his host’s home as he announced from outside, “I am letting down”. They would be invited to enter and eat with the host family. When they left, they left the bundle which contained food to replace that which they had eaten during their visit. This practise made it possible to join friends without making one’s presence a burden.

PELLKWET̓MÍN or Stay At Home Month

The Third Moon, was when the sun turns, or about January. This was usually the coldest moon of the year. During this month the Chief of the band directed the men as they went in large groups to hunt the deer in their mountain habitat. They would drive the deer into the valleys and shoot them in large numbers to take back to the village to replenish the food supply. During this month the men and their families could fish through the ice and the rivers and lakes, for trout and white fish. Small game snared now would yield soft, thick fur for a child’s robe or a grandmother’s cap. Women continued to spend many hours working side by side, sewing for the coming season.

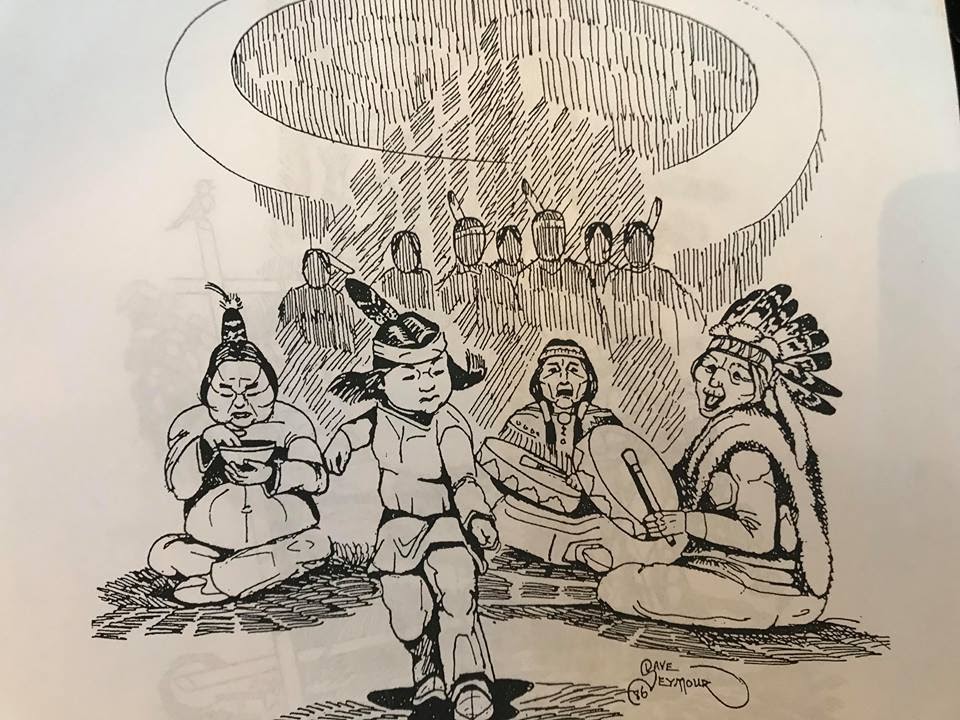

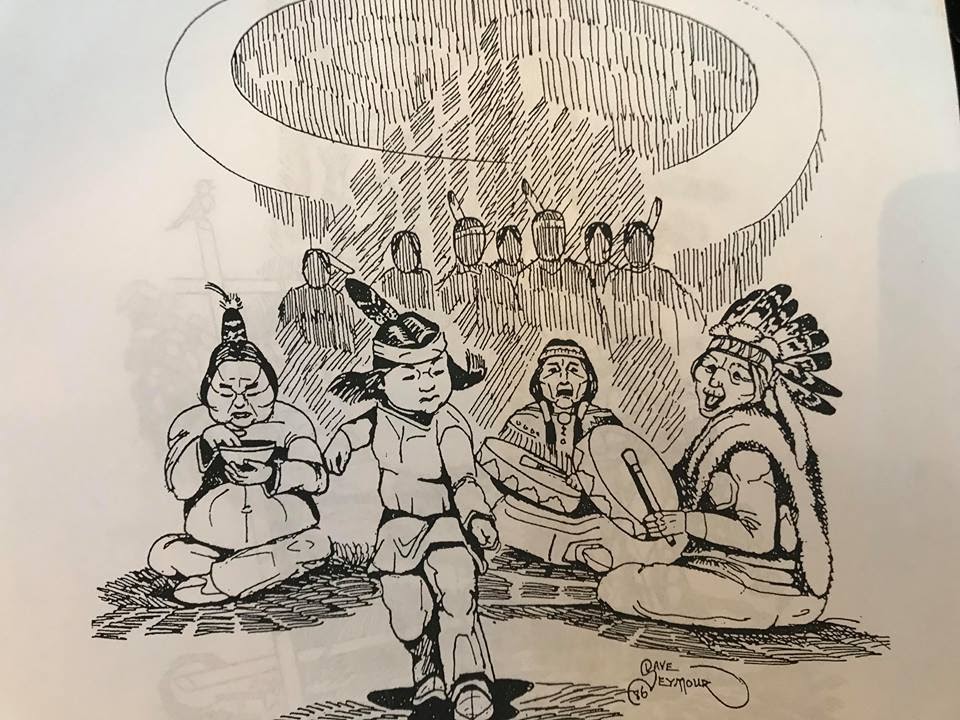

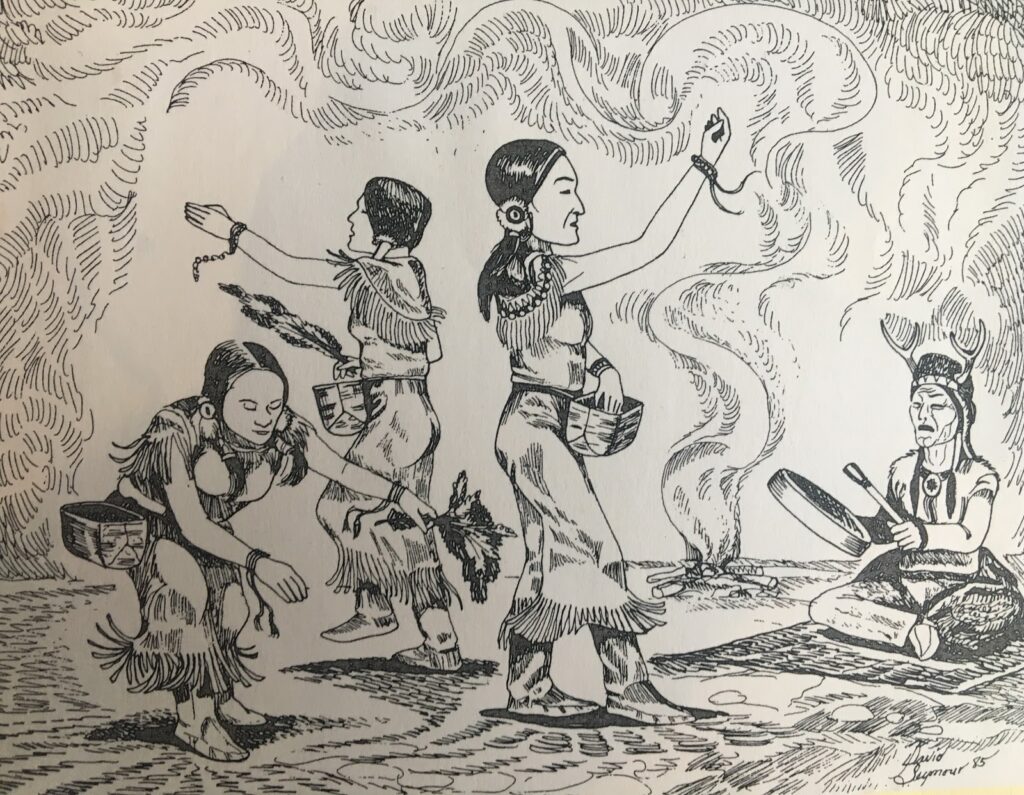

This may have been the month of winter feasting,when the hunters returned with fresh meat. All the people of the village gathered in a large home and the youths sang their mystery songs or the best song they received from their guardian spirit. A feast might occur simply because a family had a large supply of food, whereas others had little. This family would invite everyone to join them in a feast to share their food. People would play lehal and other games.

They would compete in tests of skill and endurance. Great kettles of stew, made from saskatoon, bitter-root, black tree lichen and deer grease would be available for eating whenever anyone felt hungry. Fresh roasted meat from the recent hunt would be abundant, and dried fish would be also offered. The gathering might last two to three days, and all would return to their own homes feeling satisfied with the wealth of food, fun and good companionship.

PELLCTSÍPWENTEN or Cache Pit Month

The Fourth Moon was the spring winds month, which would be around February. During this month, people would continue to trap and snare small animals. They could still fish through the ice. But the stored food supplies would be greatly reduced by the early spring month. It might be during this month that the lone hunter would rise before dawn. He’d eat a preserved berry or berry and meat cake, and, wearing his deerskin robe, leave for the mountains where the deer or elk were wintering, taking only his weapons.

He might hunt high in the mountains until he found a deer, and would drag it home over the snow to be shared with family and neighbours; a welcome change from dried food being eaten day to day. At this time, a family with a well stocked cache might be visited by the chief who would inform them of a family in need. Those with less would then be cared for, in a way that would not embarrass the family in need. If supplies were very low, the chief might call upon a group of people to forage for rose hips and black tree lichen. By this time of year, many new clothes would have been prepared from the stored hides and new hides would be prepared by tanning. People looked forward to the new growth of spring.

PESLL7ÉWTEN or Melting Month

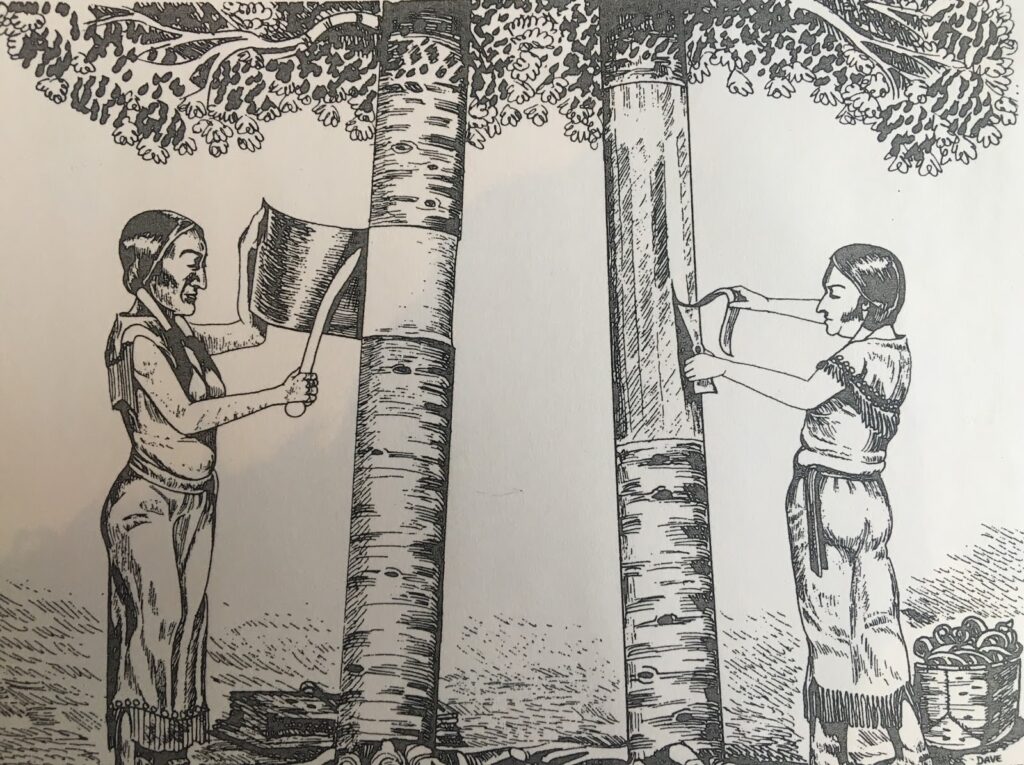

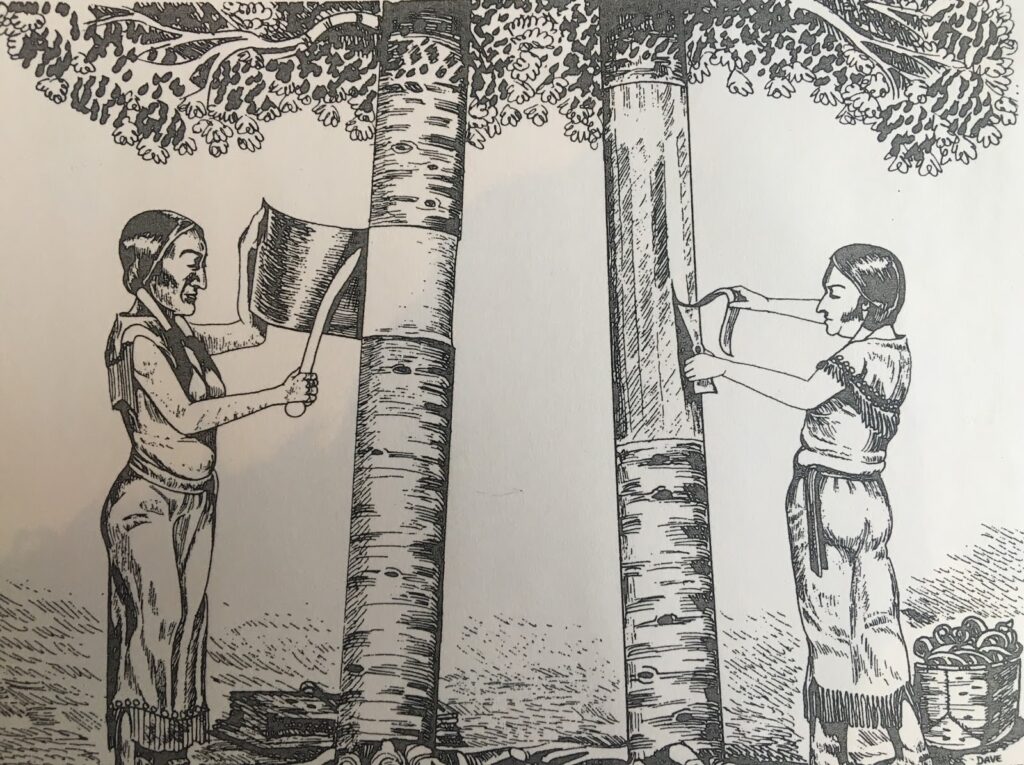

The Sixth Moon was the time when the snow disappeared from the higher ground and grass began to grow, around April. Mats of tule or bulrush were constructed or repaired to be ready for use on the summer dwellings. At this time family groups moved to their own camps in the traditional gathering places. They first dug into the ground to collect the chocolate tip shoots. Soon it was time to dig the bulbs of chocolate lily, yellow bell and lavender lily to enjoy fresh or steamed. It was also time to take the sap scrapers to the yellow pine and collect the sweet cambium and sap for the nourishment it provided. The people continued to have some fresh meat in their diet.

This was the time for collecting the cedar and spruce roots, and the bark of the birch tree for making new baskets for use and trade. Large strips of birch bark were peeled from the bigger trees and folded inside out, until they were to be made into baskets. Many metres of spruce and cedar root were uncovered and cut off, to be split and coiled for later use. Many items were stored at family caches, since not all personal items could be carried as families moved about their territory.

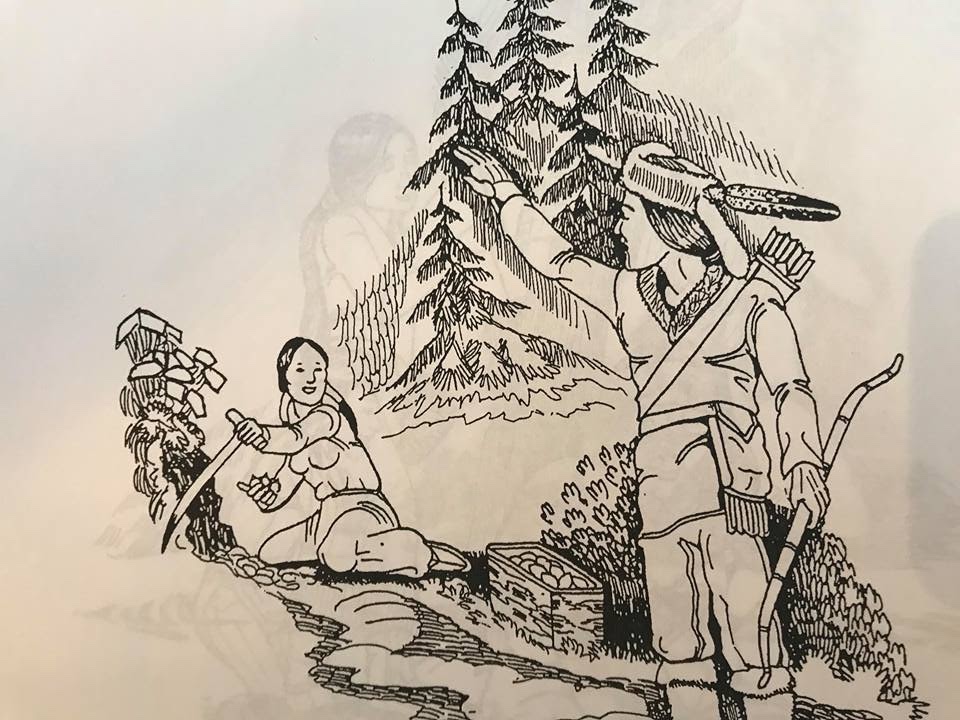

PELL7É7LLQTEN or Digging Month

The Seventh Moon was called the mid-summer month. This was about May, and the time when people fished trout in the lower lakes. Late in this month, the fish began moving into the streams and could be caught in traps or on lines in the large lakes. Hunting continued to be successful, as the deer moved out of their wintering areas on routes well known to the Secwépemc people. They could snare, trap and hunt them at their drinking and eating places in large numbers, supplying their families with fresh meat and a new source of clothing material.

It was the month when gathering began in earnest. During this month the stems of cow parsnip (Indian Rhubarb), balsamroot and fireweed were collected before they flowered and were eaten fresh or thrown into meat stews and soups as flavouring. Water parsnip bulbs were collected and prepared, as wild carrot, with its spicy flavouring. Some collected the Indian potato in large numbers at this time and stored it underground, fresh, in a cellar, where it would keep for several months. Lodgepole pine cambium was collected and eaten or dried for storage. Black cottonwood cambium and buds were eaten fresh. Strengthened and revitalized by a healthy diet of nutritious food, the Secwépemc people began to plan for major trips throughout territory, or meet old friends, and to trade goods.

PELLTSPÁNTSK or Midsummer Month

The Eighth Moon was the time when the saskatoons ripened. This month, around June, found the Secwépemc people enjoying all the fruits of summer. The saskatoon was the first of the many berries gathered and enjoyed in their area. After the chief announced the time to gather the first berries, the women gathered at the opening picking spot and picked until all the berries had been collected and preserved. They then moved as large groups, from one patch to another, as instructed by the chief, who helped to ensure that everyone knew where the berries were ripe, guiding people to these areas.

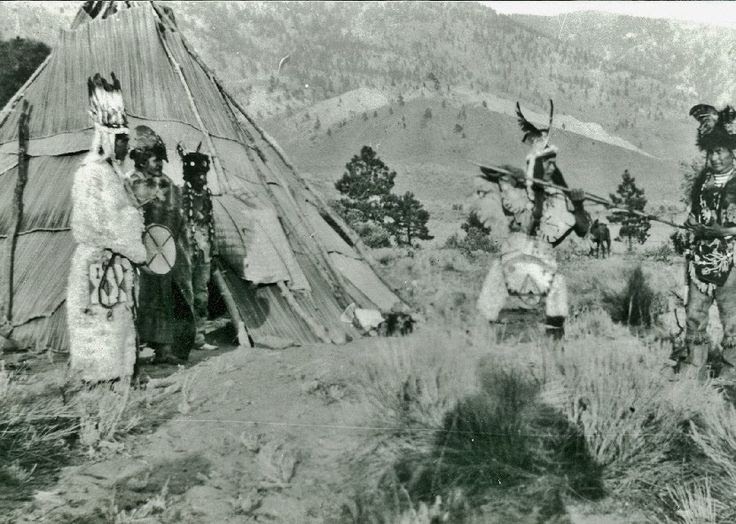

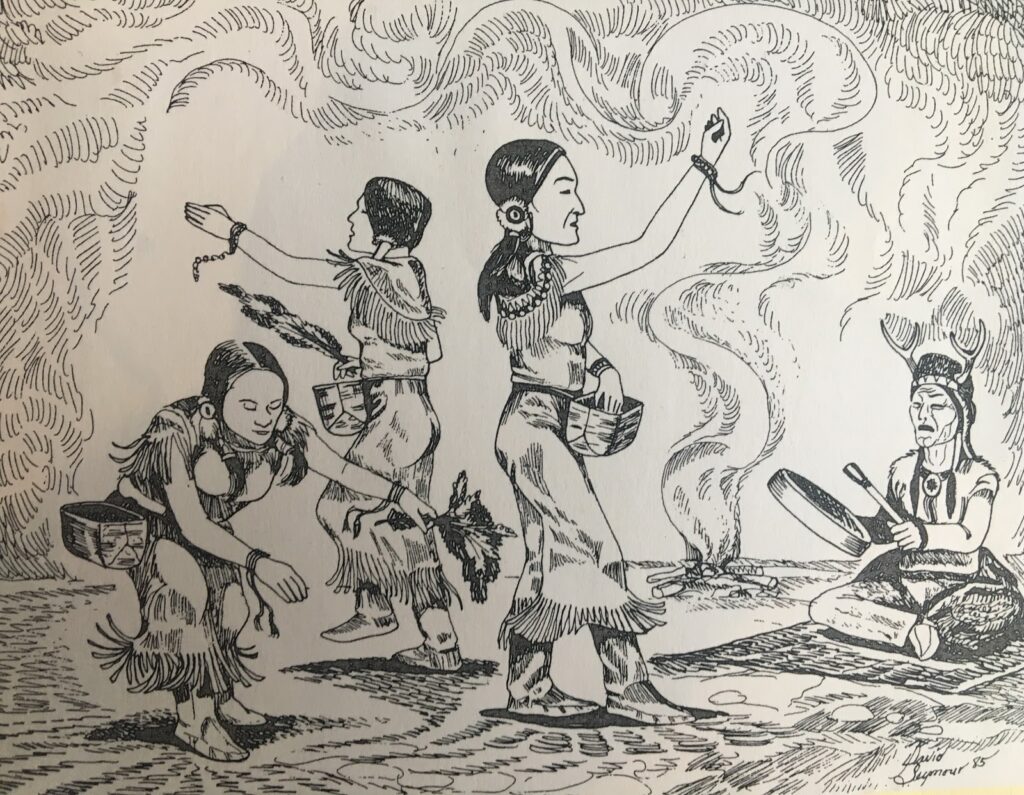

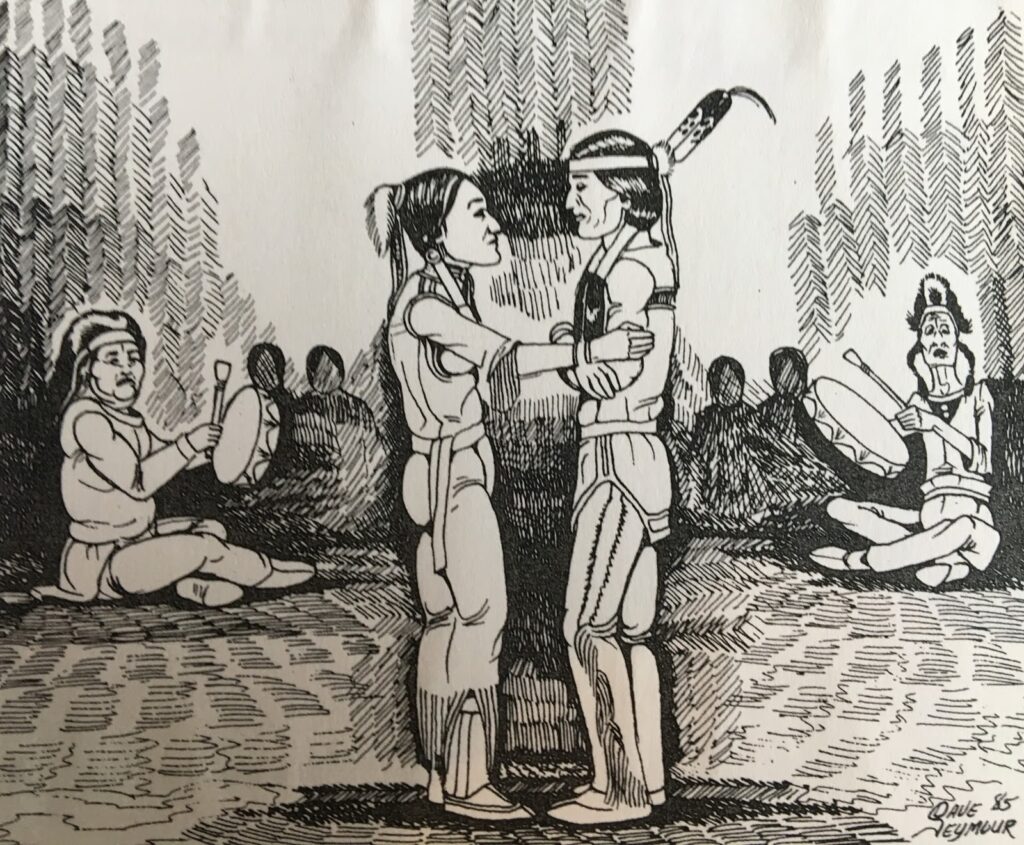

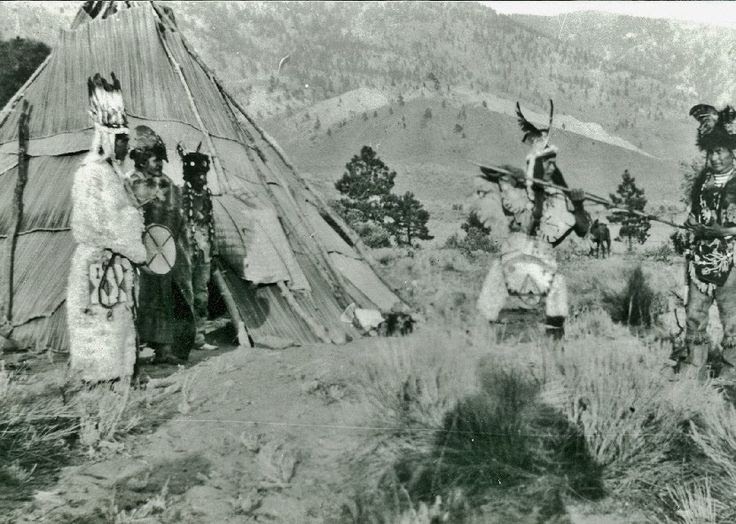

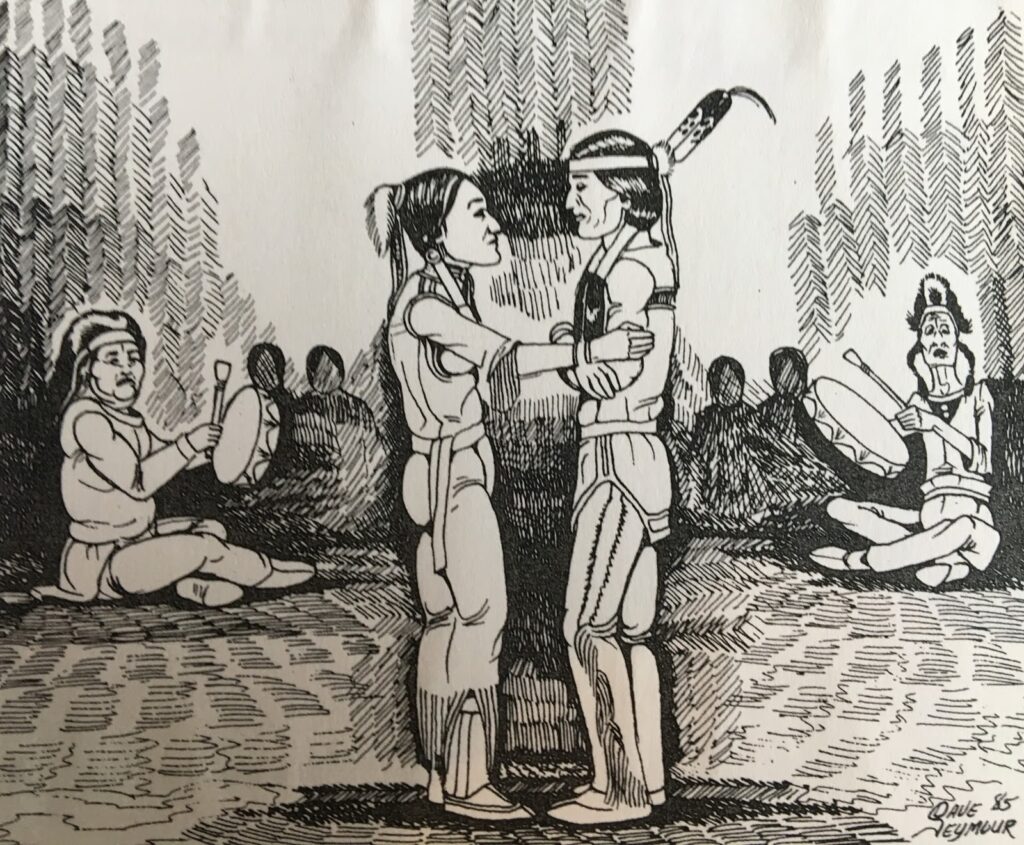

Many games took place as part of the Green Lake gathering. It was also a time when the chiefs might hold a dance which would allow the opportunity for ‘touching’, and thereby choosing a partner. Here many shared the song and dance given to them by their guardian spirits. The days could be spent in lighthearted competitions and trading, while the evenings might sometimes be involved with serious council among the elders and leaders, where the pipe was smoked and passed in the direction of the sun for guidance and to show respect.

The Secwépemc people brought many items to be traded: dried salmon, salmon oil, deer skins, marmot robes, baskets and hazelnuts to their neighbouring tribes. In return, they received bitterroot, Indian hemp bark and buffalo robes. They took moose skins from the Carrier people. From the Thompsons they got roots, salmon, Indian hemp woven baskets, parfleche and wampum beads. They traded for salmon, woven baskets, goat hair robes and deer skins with the Lillooet people.

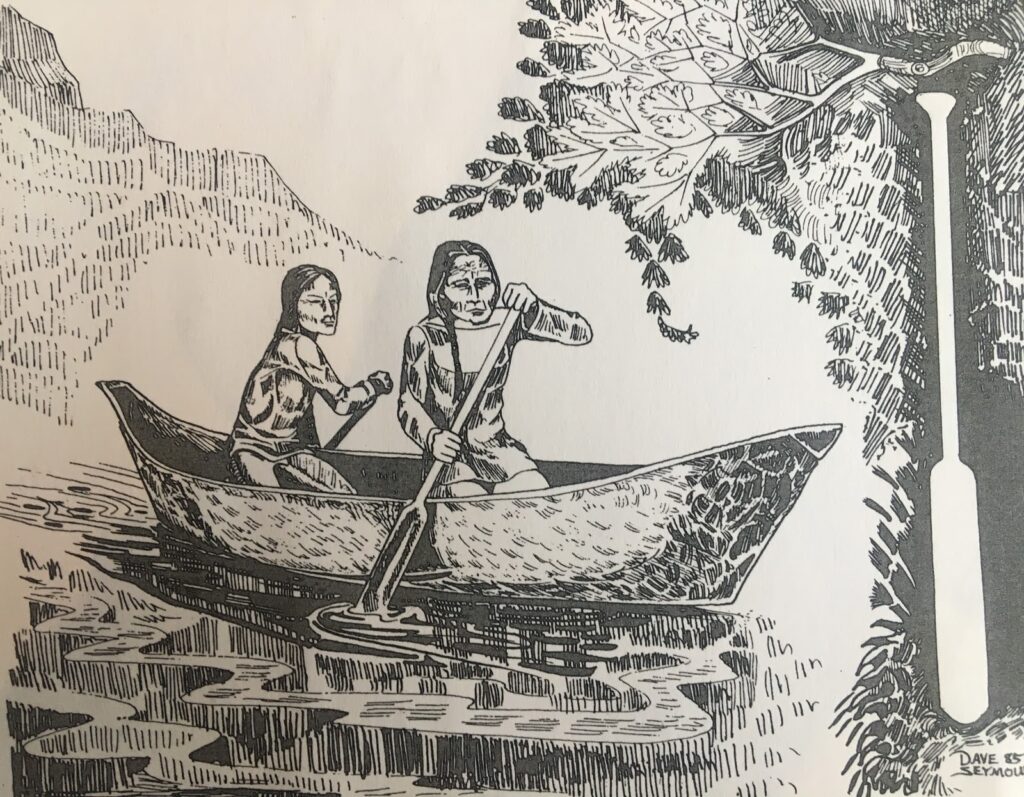

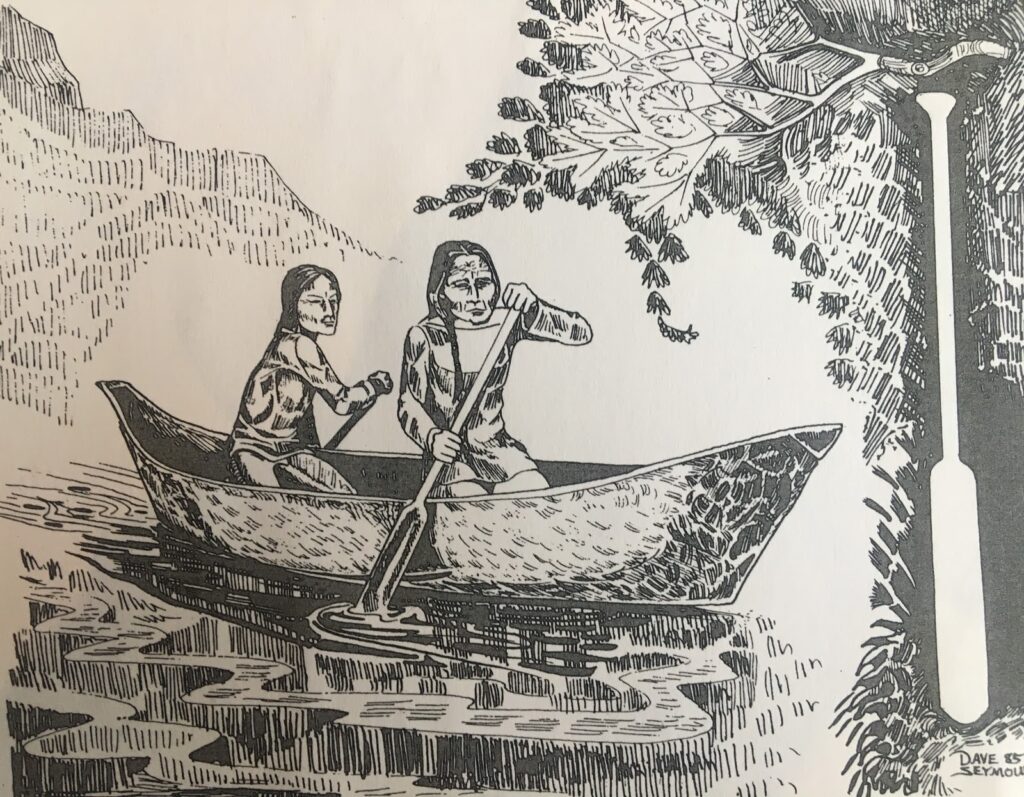

Through the summer season, the Secwépemc people would have travelled greatly among their divisions.They used the rivers within their territory to move swiftly from place to place, and walked long distances over land to communicate with their neighbouring tribes. Although the language from group to group differed, they used sign language to express themselves and developed a common language, the Chinook Jargon, to talk to each other (a trade language).

The Secwépemc of the Upper North Thompson, Shuswap Lake and on Arrow Lake were the most isolated, and the Tk’emlups people travelled most widely. The fairly regular intermingling between Secwépemc villages and between Secwépemc and non-Secwépemc people resulted in intermarriage and a resulting extension of ties, since kinship ties were very important to the Secwépemc people.

PELLC7ELLCW7ÚLLCWTEN

Entering Pithouses Month

First Moon was when people moved into their winter homes. It was also the time when the deer ran, so some hunting was being carried out. The First Moon was in November, by our present calendar. At this time the Secwepemc people from all over moved into their winter villages by the rivers. Peoples’ caches, both above and underground, were located and filled with bounty of their summer and fall work. Here too, along the banks near the village, appeared the sweathouses, where they could regularly cleanse themselves, both physically and spiritually.

Along the Shuswap Lake, Canim Lake, the South Thompson, the North Thompson, and the Bonaparte River valleys, people were building or rebuilding winter dwellings that would be comfortable throughout the winter. When people had moved into their winter homes, the hunting chief would call the men to hunt elk or deer in the nearby hills. The hunters would travel in small groups and call the male game with bone calls or by imitating them, attracting the animals. The meat brought into the village was shared among the hunters’ families and dried above the fires, to be later added to the caches which held large supplies of winter food.

During this moon, storytelling would begin, to shorten the long evenings that were part of winter season. Precious chunks of dried strawberry or saskatoon cake could be enjoyed as the elders of the families spent hours telling the stories of their ancestors to the younger members. Young children would drift into sleep to the sound of their grandparents’ voice recounting the tales and truths of the Secwépemc way of life.

PELLTETÉQEM

Crossover Month

The Second Moon, was the time of first real cold, around December. At this time, people were well settled for winter. The men continued to go out on hunting trips alone or in small groups, bringing back more deer for drying and eating fresh. Women and children helped to set traps and snares for small animals near the village site, catching rabbits and other small animals. The food for a day of trapping might be a dried cake of meat and berries and some dried salmon.

Women took skins from storage and began work on the winter clothing and all garments needed for the coming year. Many hours were spent by the women, sewing together by firelight. Each day, women and children collected wood to keep the house fire burning and water from the lake or river, for cooking and cleaning. A constantly burning fire would warm deer meat stews and berry cake mixed with deer grease, or soups thickened with black tree lichen.

During this month a group of young would plan a visit, to a neighbouring village, or to other members of the same village. One was for the visitor to lower a bundle into his host’s home as he announced from outside, “I am letting down”. They would be invited to enter and eat with the host family. When they left, they left the bundle which contained food to replace that which they had eaten during their visit. This practise made it possible to join friends without making one’s presence a burden.

PELLKWET̓MÍN

Stay At Home Month

The Third Moon, was when the sun turns, or about January. This was usually the coldest moon of the year. During this month the Chief of the band directed the men as they went in large groups to hunt the deer in their mountain habitat. They would drive the deer into the valleys and shoot them in large numbers to take back to the village to replenish the food supply. During this month the men and their families could fish through the ice and the rivers and lakes, for trout and white fish. Small game snared now would yield soft, thick fur for a child’s robe or a grandmother’s cap. Women continued to spend many hours working side by side, sewing for the coming season.

This may have been the month of winter feasting,when the hunters returned with fresh meat. All the people of the village gathered in a large home and the youths sang their mystery songs or the best song they received from their guardian spirit. A feast might occur simply because a family had a large supply of food, whereas others had little. This family would invite everyone to join them in a feast to share their food. People would play lehal and other games.

They would compete in tests of skill and endurance. Great kettles of stew, made from saskatoon, bitter-root, black tree lichen and deer grease would be available for eating whenever anyone felt hungry. Fresh roasted meat from the recent hunt would be abundant, and dried fish would be also offered. The gathering might last two to three days, and all would return to their own homes feeling satisfied with the wealth of food, fun and good companionship.

Cache Pit Month

PELLCTSÍPWENTEN

Cache Pit Month

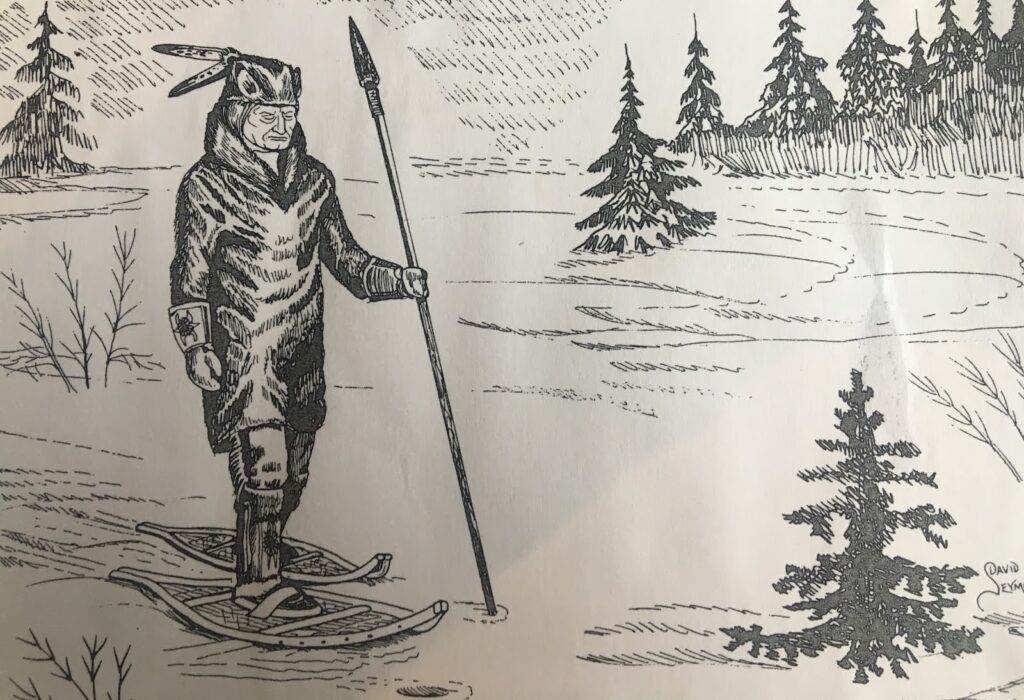

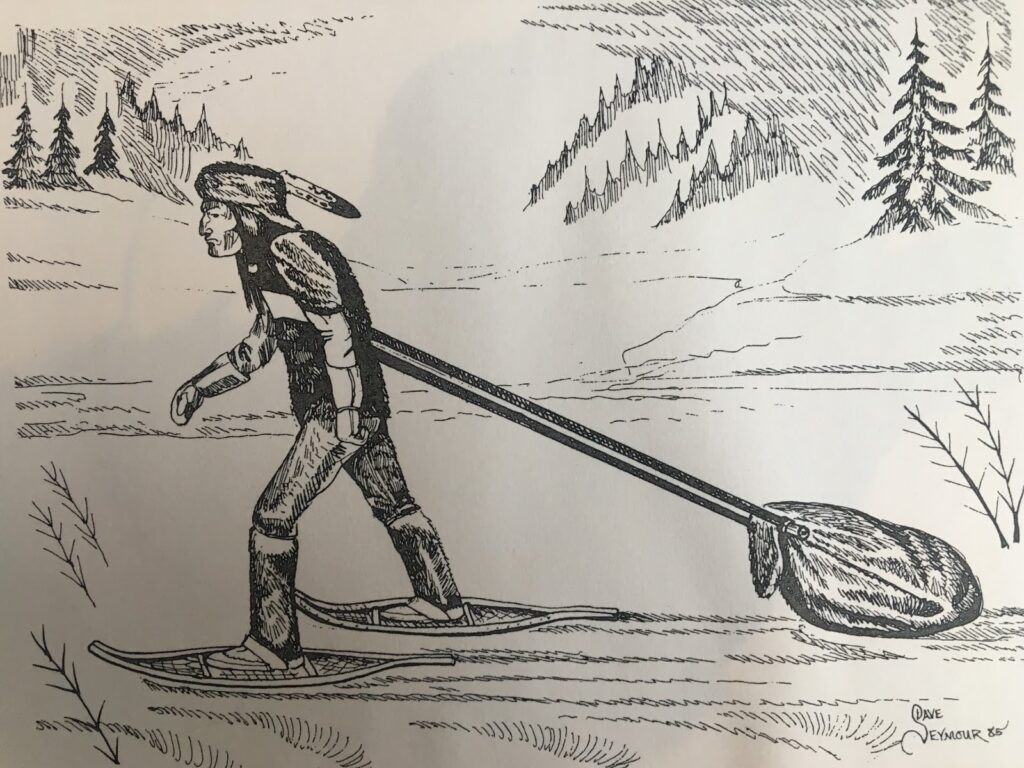

The Fourth Moon was the spring winds month, which would be around February. During this month, people would continue to trap and snare small animals. They could still fish through the ice. But the stored food supplies would be greatly reduced by the early spring month. It might be during this month that the lone hunter would rise before dawn. He’d eat a preserved berry or berry and meat cake, and, wearing his deerskin robe, leave for the mountains where the deer or elk were wintering, taking only his weapons.

He might hunt high in the mountains until he found a deer, and would drag it home over the snow to be shared with family and neighbor’s; a welcome change from dried food being eaten day to day. At this time, a family with a well stocked cache might be visited by the chief who would inform them of a family in need. Those with less would then be cared for, in a way that would not embarrass the family in need. If supplies were very low, the chief might call upon a group of people to forage for rose hips and black tree lichen. By this time of year, many new clothes would have been prepared from the stored hides and new hides would be prepared by tanning. People looked forward to the new growth of spring.

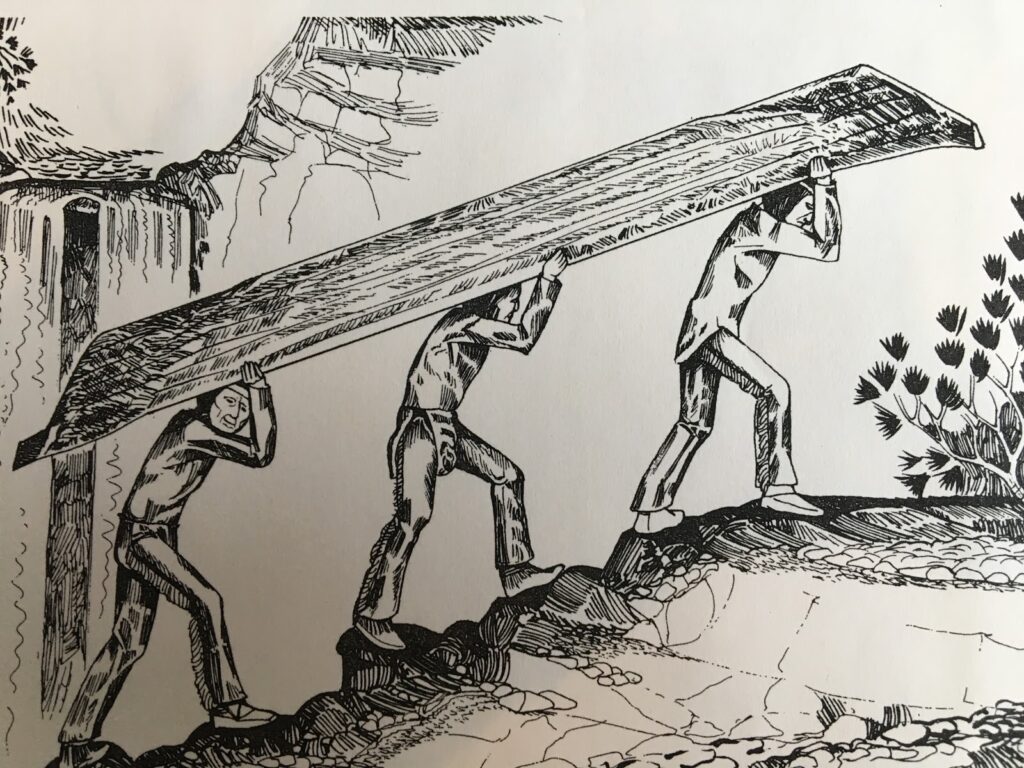

PELLSQÉPTS Spring Month

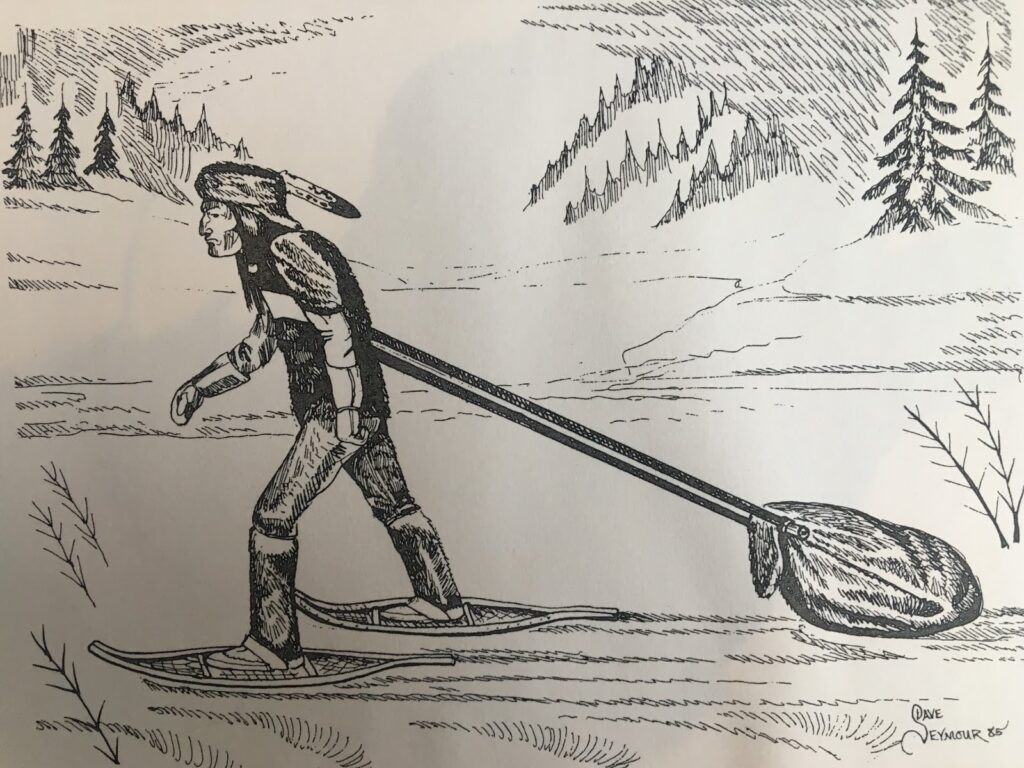

The Fifth Moon, little summer month (March), was when the snow began to disappear from the lower grounds. By the end of this moon, some of the people were moving out of their winter homes. Winter stores would be at their lowest. Fishing through the ice would no longer be safe by the end of this month. People would be looking forward to moving out into their digging, hunting and fishing areas. They might be beginning to slice huge rounds of cottonwood, spruce or cedar from the trees, to shape into canoes in readiness for travel on the lakes and rivers.

The women would be busy sewing and repairing the storage bags and tumplines that were used as they began traveling from place to place gathering roots, shoots and berries. Now deer hunting could be done in the mountains on the crust. The successful hunter would have been a welcome sight in his village and the food enjoyed by all. People were excited to move out of the villages. Households would gather all their possessions to prepare to move into the gathering areas, at the slightly higher elevations.

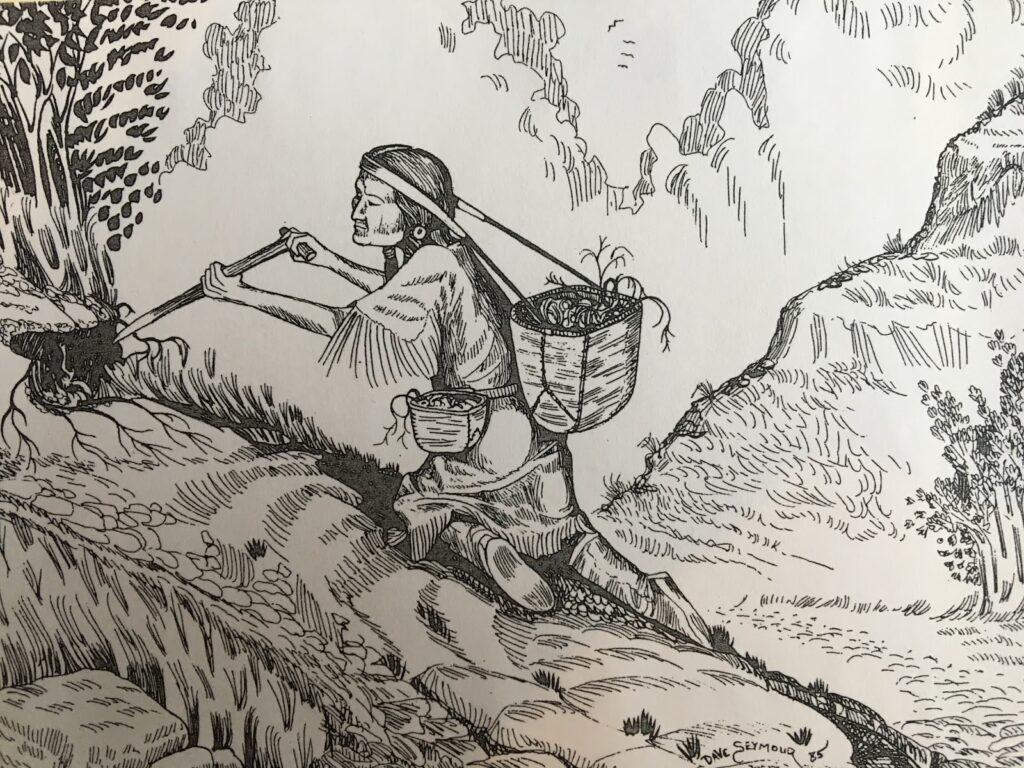

By the end of the moon, women were out digging with sticks, under dead stems of balsam root for the tender shoots which had just begun to grow underground. These, most plentiful in the drier regions of Secwépemc territory, could be taken home and offered fresh to children and the elderly, as the first fresh source of vitamins in many months.

PESLL7ÉWTEN Melting Month

The Sixth Moon was the time when the snow disappeared from the higher ground and grass began to grow, around April. Mats of tule or bulrush were constructed or repaired to be ready for use on the summer dwellings. At this time family groups moved to their own camps in the traditional gathering places. They first dug into the ground to collect the chocolate tip shoots. Soon it was time to dig the bulbs of chocolate lily, yellow bell and lavender lily to enjoy fresh or steamed. It was also time to take the sap scrapers to the yellow pine and collect the sweet cambium and sap for the nourishment it provided. The people continued to have some fresh meat in their diet.

This was the time for collecting the cedar and spruce roots, and the bark of the birch tree for making new baskets for use and trade. Large strips of birch bark were peeled from the bigger trees and folded inside out, until they were to be made into baskets. Many metres of spruce and cedar root were uncovered and cut off, to be split and coiled for later use. Many items were stored at family caches, since not all personal items could be carried as families moved about their territory.

PELL7É7LLQTEN Digging Month

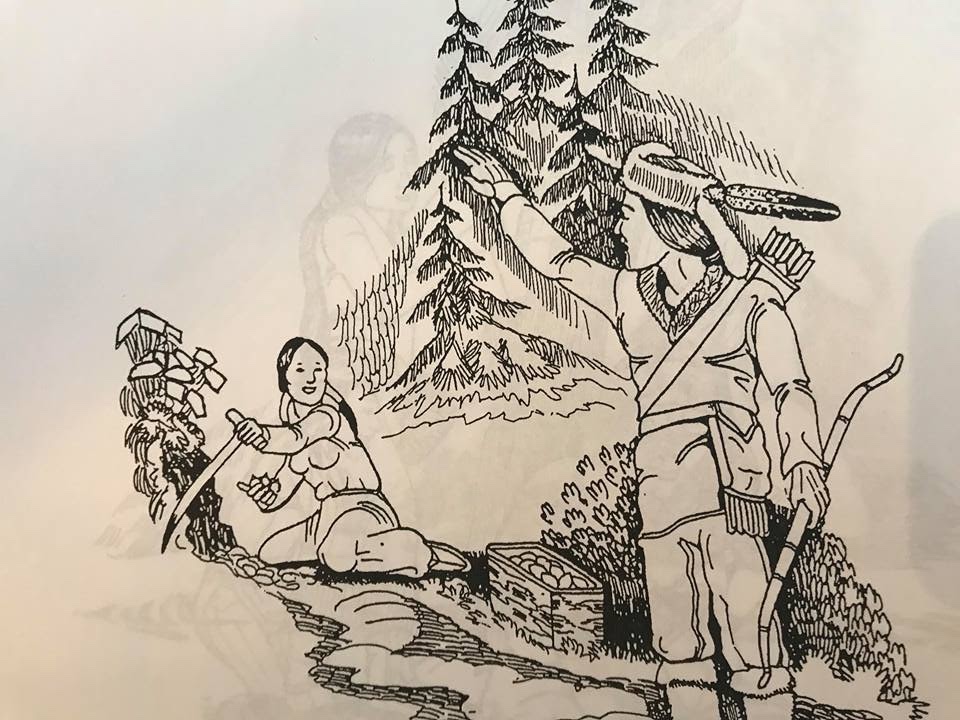

The Seventh Moon was called the mid-summer month. This was about May, and the time when people fished trout in the lower lakes. Late in this month, the fish began moving into the streams and could be caught in traps or on lines in the large lakes. Hunting continued to be successful, as the deer moved out of their wintering areas on routes well known to the Secwépemc people. They could snare, trap and hunt them at their drinking and eating places in large numbers, supplying their families with fresh meat and a new source of clothing material.

It was the month when gathering began in earnest. During this month the stems of cow parsnip (Indian Rhubarb), balsamroot and fireweed were collected before they flowered and were eaten fresh or thrown into meat stews and soups as flavouring. Water parsnip bulbs were collected and prepared, as wild carrot, with its spicy flavouring. Some collected the Indian potato in large numbers at this time and stored it underground, fresh, in a cellar, where it would keep for several months. Lodgepole pine cambium was collected and eaten or dried for storage. Black cottonwood cambium and buds were eaten fresh. Strengthened and revitalized by a healthy diet of nutritious food, the Secwépemc people began to plan for major trips throughout territory, or meet old friends, and to trade goods.

PELLTSPÁNTSK Midsummer Month

The Eighth Moon was the time when the saskatoons ripened. This month, around June, found the Secwépemc people enjoying all the fruits of summer. The saskatoon was the first of the many berries gathered and enjoyed in their area. After the chief announced the time to gather the first berries, the women gathered at the opening picking spot and picked until all the berries had been collected and preserved. They then moved as large groups, from one patch to another, as instructed by the chief, who helped to ensure that everyone knew where the berries were ripe, guiding people to these areas.

Many games took place as part of the Green Lake gathering. It was also a time when the chiefs might hold a dance which would allow the opportunity for ‘touching’, and thereby choosing a partner. Here many shared the song and dance given to them by their guardian spirits. The days could be spent in lighthearted competitions and trading, while the evenings might sometimes be involved with serious council among the elders and leaders, where the pipe was smoked and passed in the direction of the sun for guidance and to show respect.

The Secwépemc people brought many items to be traded: dried salmon, salmon oil, deer skins, marmot robes, baskets and hazelnuts to their neighbouring tribes. In return, they received bitterroot, Indian hemp bark and buffalo robes. They took moose skins from the Carrier people. From the Thompsons they got roots, salmon, Indian hemp woven baskets, parfleche and wampum beads. They traded for salmon, woven baskets, goat hair robes and deer skins with the Lillooet people.

Through the summer season, the Secwépemc people would have travelled greatly among their divisions.They used the rivers within their territory to move swiftly from place to place, and walked long distances over land to communicate with their neighbouring tribes. Although the language from group to group differed, they used sign language to express themselves and developed a common language, the Chinook Jargon, to talk to each other (a trade language).

The Secwépemc of the Upper North Thompson, Shuswap Lake and on Arrow Lake were the most isolated, and the Tk’emlups people travelled most widely. The fairly regular intermingling between Secwépemc villages and between Secwépemc and non-Secwépemc people resulted in intermarriage and a resulting extension of ties, since kinship ties were very important to the Secwépemc people.